|

| Réunion de musiciens by François Puget traditionally believed to depict Jean-Baptiste Lully (holding the violin) and Philippe Quinault (playing the lute) surrounded by other musicians at the court of Louis XIV. The painting is held in the Musée du Louvre. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In the middle of the nineteenth century, there was a great revolution in instrument making. Actually, many of these changes had been slowly taking place over the course of a century or so, especially with the string instruments. However, the style of music in the late eighteenth century probably had some influence on the evolution of the instruments of the orchestra. Extreme contrasts of dynamics were called for in the music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Although that was, no doubt, an important factor behind the desire to manufacture louder instruments, with more dynamic range, I believe that it was not the only factor.

There was another reason for the nineteenth-century preoccupation with increasing the dynamics of instruments. Audiences were getting larger and concert halls were getting larger in order to accommodate these larger audiences. Orchestras were required to produce a greater volume of sound to fill the new concert halls. Making orchestras larger was simply not the answer. Larger orchestras have a hard time playing fast tempi with precision. This is why Beethoven preferred a forty-piece orchestra for his symphonies when he could have had them performed by a sixty-piece orchestra. The choice between using a large or small orchestra to perform a given composition, of course, boils down to how big the string section is.

The number of woodwinds and brass is determined by the score, but you can have as big or as small a string section as you like. The standard orchestra of the late eighteenth century consists of first violins, second violins, violas, cellos, string basses, two oboes, two bassoons, two kettle drums, sometimes two or three horns, sometimes a trumpet or even two, and two flutes. By 1800 two clarinets had also become a standard part of the orchestra. What follows is a discussion of the differences between modern orchestral instruments and their earlier counterparts, with an emphasis on the development of the string instruments.

The Violin

The first thing I would like to discuss is the violin bow. The original violin bow, when the instrument was first invented by Amati, in 1550, was shaped more or less like a hunting bow. It had a pronounced arch to it, and the hairs were rather slack. The tension of the hairs was controlled by subtle movements of the bowing hand. This made it easy to bow all four strings at the same time, or one at a time when necessary. When the player wanted to bow three or four strings, he would slacken the bow hairs a bit. When he wanted to bow one or two, he would increase the tension a bit. This type of bow had changed little in the time of Bach.

Another thing that made it easier to bow all four strings at once, was the fact that the bridge was not quite as arched as that of a modern violin, thus putting the strings closer to being in the same plane. On a modern violin, one can bow three strings simultaneously, but it is difficult to do this without giving greater pressure, and therefore greater loudness, to the string in between the other two. Modern violinists have to sort of fake it, when they play Bach's sonatas and partitas for unaccompanied violin. When Bach calls for four notes to be played simultaneously, the player of a modern violin will rapidly move the bow, one string at a time, causing the notes to be heard in rapid succession, one after the other, closing approximating the sound that one would get from bowing all four notes at once. On the violin of Bach's day, this technique wasn't necessary, as the bow could easily be moved across all four strings simultaneously.

The violin bow underwent a gradual change throughout the eighteenth century, becoming less and less arched. At the end of the eighteenth century, a man named Tourte created a new style of bow. This bow actually curved slightly toward the hairs, instead of away from them. This new bow could play much louder than the old baroque bow. Also, unlike the baroque bow, this new bow could produce an equally loud volume along its entire length. With this new bow, a skilled violinist could make the change from upbow to down-bow almost imperceptible. It was perfectly suited to the new style of music, with its broad, sweeping melodic lines. The same reasons that make the Tourte bow so well suited for nineteenth-century music make it somewhat unsuitable for eighteenth-century music, especially early eighteenth-century music.

|

| Hornviolin (trumpet-violin) together with a normal violin (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

The old baroque bow produced a strong sound in the middle of its length, the sound getting much weaker as the string was approached by either end of the bow. This is actually an advantage when performing baroque music, with its highly articulated phrasing and lean texture. The old baroque bow allowed more nuances of shaping a note. With the Tourte bow, it is hard to shorten a note without making it sound chopped off. And with most baroque music, it is advantageous to make the up-bow sound different from the down-bow. The old baroque bow is much better suited to the lean, transparent textures of the baroque music. In polyphonic music, it is easier to hear all of the individual lines if each player does not smoothly connect his or her notes, but allows a bit of "space" between them. This is possible on a modern violin but comes naturally with a baroque violin.

The body of the violin went through major changes in the middle of the nineteenth century. A chin rest was added by Louis Spohr early in the nineteenth century, resulting in a whole new technique of playing. The strings were made thicker, and eventually were wound with metal, the sound post was made thicker, the bass bar was made thicker and stronger, and much more tension was put on the strings. With the thicker strings, the bow has to be drawn over the strings with much more pressure in order to get them to vibrate, but the sound is much louder. The neck, instead of coming straight out from the belly, was glued on at an angle, which makes the angle of the strings across the bridge acuter.

All of these changes resulted in a tremendous loss of overtones, resulting in a much dryer sound. This is why the old baroque violin has such a sweet, pretty sound when compared to a modern violin. This is the price that was paid in order to increase the volume of the instrument. With the new instrument, dynamics became the dominant means of achieving a variety of expression, while nuances of articulation were the main means of achieving expressive variety with the baroque violin. Also, a musician playing a modern violin, in order to compensate for the inherently dry sound, will make almost constant use of vibrato, a technique, which was only used sparingly, and only for special effect, in the eighteenth century.

Eighteenth-century books on violin playing, including the one by Leopold Mozart, tell us that vibrato should sometimes be used to add spice to a note. Vibrato is the daily bread and butter of the modern violinist. It is used almost constantly. Without it, the sound would be dull and dry. I should mention here that I am speaking of the fingered vibrato, not the bowed vibrato. The bowed vibrato is produced by a rapid pulsation of the bow across the strings. This effect was rather common in the Baroque period and is meant to imitate the tremulant in organs.

In the middle of the nineteenth century great instruments built by the great masters of old, such as Stradivari, Gaunari, and Stainer, to name the three most important, were taken apart and rebuilt in an effort to make them like the newer violins. Many of them literally broke in two from the strain. There are no instruments built by the great masters, that have not been rebuilt, some of them many times over. In my opinion, this is a great tragedy.

Everything that has been said above about the violin is also largely true of the viola and cello. The bass violin had a somewhat different history. In Germany, in the eighteenth century, a three-stringed bass was commonly used. The Germans discovered that a bass with only three strings had a beautiful, more pure sound than one with four. However, the more versatile four string bass become the norm and the three string bass became obsolete.

Woodwinds

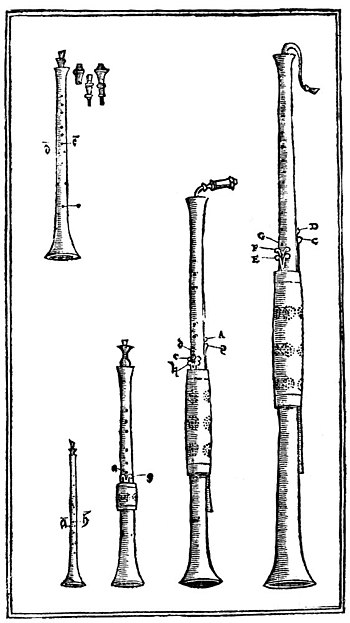

|

| A Shawn. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

The woodwinds also underwent a complete makeover in the nineteenth century. The taper of the internal bore also was changed. This resulted in a louder instrument with a different timbre than the old ones. The old baroque woodwinds had seven or eight holes. Six holes were closed directly by the fingers and the others were closed by keys. In the modern woodwind, all of the holes are closed by keys. Due to the nature of the arrangement of the holes, and mostly because of the fact that they are closed directly by the fingers, each woodwind is easily playable in one certain key and is progressively more difficult to play in keys that are more and more distantly related to the basic key of the instrument. The modern woodwinds, with the key mechanisms used to cover the holes, instead of being covered directly by the fingertips, are just as easy to play in one key as in another. Besides equal ease of playing in all keys, another important difference it that every note on a modern woodwind has pretty much the same timbre, while on a baroque woodwind, especially the flute, each tone will have a noticeably different timbre.

In the clarinet and oboe, the internal bore was widened. The end bell of the clarinet became less flared. This resulted in a different sound. The bassoon of the eighteenth century was constructed differently too, the main difference being the walls of the instrument were thin enough to vibrate. This is an important difference. The laws of acoustics dictate that the timbre of a wind instrument is not affected by the material it is made from as long as the walls of the instrument are to think to vibrate. The thinness of the wooden tube out of which the old bassoons were made gave it a sweeter sound, but the new bassoons were much louder.

Brass

The main change in the brass instruments was the invention of valves which are operated by pressing levers with the fingers. This made the instruments much more versatile. With the old brass instruments, the player had to change the tension of his lips to make different notes, the only notes being available being the ones of the harmonic overtones. Horn players employed short lengths of tubing called crooks. In order to play in a different key, the horn player removed one crook and inserted another. This was a bit cumbersome and composers rarely asked for horn players to change crooks within a movement, though they usually had to change crooks between movements.

Horn players in Mozart's day had figured out that they could change a note by a semitone by inserting their fist carefully into the end bell and holding it just right. This gave them the ability to play things that they could not otherwise play, but this technique was used sparingly because of the difference in timbre of the not thus produced. The invention of valves gave all of the brass much more versatility. In the late eighteenth century, the trumpet was outfitted with one valve, which was controlled by the thumb. This enabled the trumpet player to play a lot more notes. It was this type of trumpet for which Josef Haydn composed his famous trumpet concerto. In the nineteenth century, three valves which control the airflow through sections of tubing were added to the trumpet, allowing the player much more versatility. The trombones, of course, did not need to be outfitted with valves because they always had a slide which changed the length of the vibrating column of air, thus changing the note.

The smaller internal bore of the old brass instruments gave them, well, no pun intended, a brassier sound. The trumpets had more of a bite to their sound. The horns were a bit harsh compared to the smooth sounding modern horn. The trombones had a slightly harsh edge to their sound compared to modern trombones.

Pros and cons

So which is better, the old baroque instruments of modern ones? I don't think either is better. They are only different. The old instruments have a sweet sounding quality that comes through even in recordings. They are perfectly suited to the music of Bach and Handel. They are great on recordings but they will never have an important place in the modern concert world because their sound is too weak to fill a big concert hall. While it is possible to do justice to the music of Bach and Handel on modern instruments if the musicians have an intimate understanding of the style, it would be sheer madness to play Strauss or Debussy on baroque instruments.

As for the music of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven, it is easy to make the argument that it should be played on the same type of instruments they had in their time, and maybe certain aspects of their music to+-+ come through more clearly on the old instruments. But it is also easy to argue that their music pushed the instruments of their time to their limits, and even beyond. Their music was revolutionary. It was ahead of its time in many ways, especially the music of Beethoven. Why should we have to put up with the limitations that were forced on them when we can hear their music played very effectively with modern instruments?

Ultimately, it is the skill, understanding, and sensitivity of the musicians to the style of music that they are playing that makes the biggest difference, not the type of instruments they are playing.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment