|

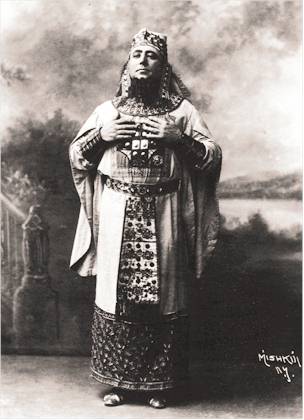

| Richard Wagner, (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

Wagner's Goetterdaemmerung completes the operatic tetralogy 'The Ring of the Nibelung', an allegory of greed and power set to addictive music of considerable complexity. In a nutshell: Siegfried, after rejecting his betrothed Bruennhilde, succumbs through Hagen's treachery to the curse Alberich has put on the ring, whereupon Bruennhilde returns the ring to the Rhine and causes the destruction of Valhalla, the new home of the corrupted gods.

The Goetterdaemmerung broadcast from Melbourne (13.12.13, the final night of the third Melbourne cycle) is very disappointing so far, not matching up to the hype at all. Pietari Inkinen's orchestral opening had no mystery. Tired, unruly, small voices were not able to convince in the Prologue. The orchestra was much too prominent. Siegfried's horn call lacked boisterous enthusiasm and the performance of his Rhine journey by the orchestra was pedestrian. Hagen and Gunther have redeemed things vocally somewhat in Act I and the blood-brotherhood duet between Siegfried and Gunther was powerfully delivered. Bruennhilde's sister Waltraute (Deborah Humble) at last injected some drama into the proceedings.

I am hoping for mystery at the beginning of Act II. In the event, at least on the radio, Warwick Fyfe as Alberich has a live presence, no figment of the sleepy Hagen's imagination. He makes Alberich's complex music portray sharply the dwarf's dangerous and elemental nature.

Hagen's famous call to the vassals was tremulous, but introduced real excitement into the wedding and revenge scenes. Susan Bullock as Bruennhilde sounded genuinely shocked and distressed. Barry Ryan's regal anger as Gunther was also evident. The revenge trio was a vocal and dramatic climax to the Act.

Superb singing from the Rhine maidens at the beginning of Act III. Apparently, they are dressed like Follies; I think I am glad I can't see the production (I'm watching The Ashes cricket concurrently, with the TV's sound off).

Siegfried's Erzaehlung is going very well (I'm taking a leaf out of a cricket commentator's book); Stefan Vinke has now warmed up vocally, and the orchestral accompaniment has receded into the background: perhaps he's right at the front of the stage.

Hagen's 'Meineid raechte ich' descended totally into melodrama, but Vinke has restored the intensity with the conclusion of his monologue. The orchestra have at last excelled themselves in Siegfried's funeral music and Susan Bullock has found opportunities for a chamber-music restraint, rich with sorrow. Her Immolation is shaping up to be the emotional and vocal high point of the performance. The orchestral playing at the conclusion, offering hope for the future of mankind, is powerful and convincing.

What a trajectory. Rather like Australia's first innings in Perth.

Article Source: EzineArticles |