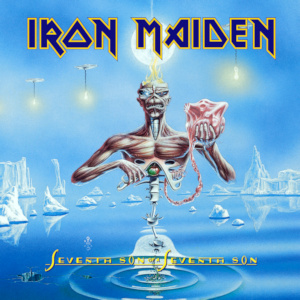

A five string electric violin. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

An annoyed grimace spread across my conductor's face upon hearing a Bach concerto played with crunchy distortion in the band room before an orchestra rehearsal.

Expecting to find a headbanger guitarist mocking the establishment by shredding away at a time-honoured classic, his fury slowly melted into a pitying look of concern and sad loss, as if inside his head he was thinking, “Dear God, there goes another one.”

My dad had bought me an electric violin and I was making heads turn with my heavy variations on the classics.

The Zeta Strados Modern violin, with its funky profile, maple flame finish and revolutionary bridge pickup design, has been the height of electric violin technology for some time. Technology aside, this violin made it possible for me to be regarded as cool by my peers, even though I was still playing music by dead guys with wigs.

My model even had five strings, which made it more of a violin/viola hybrid, the low range is perfect for raunchy power chords and guitar-like riffs.

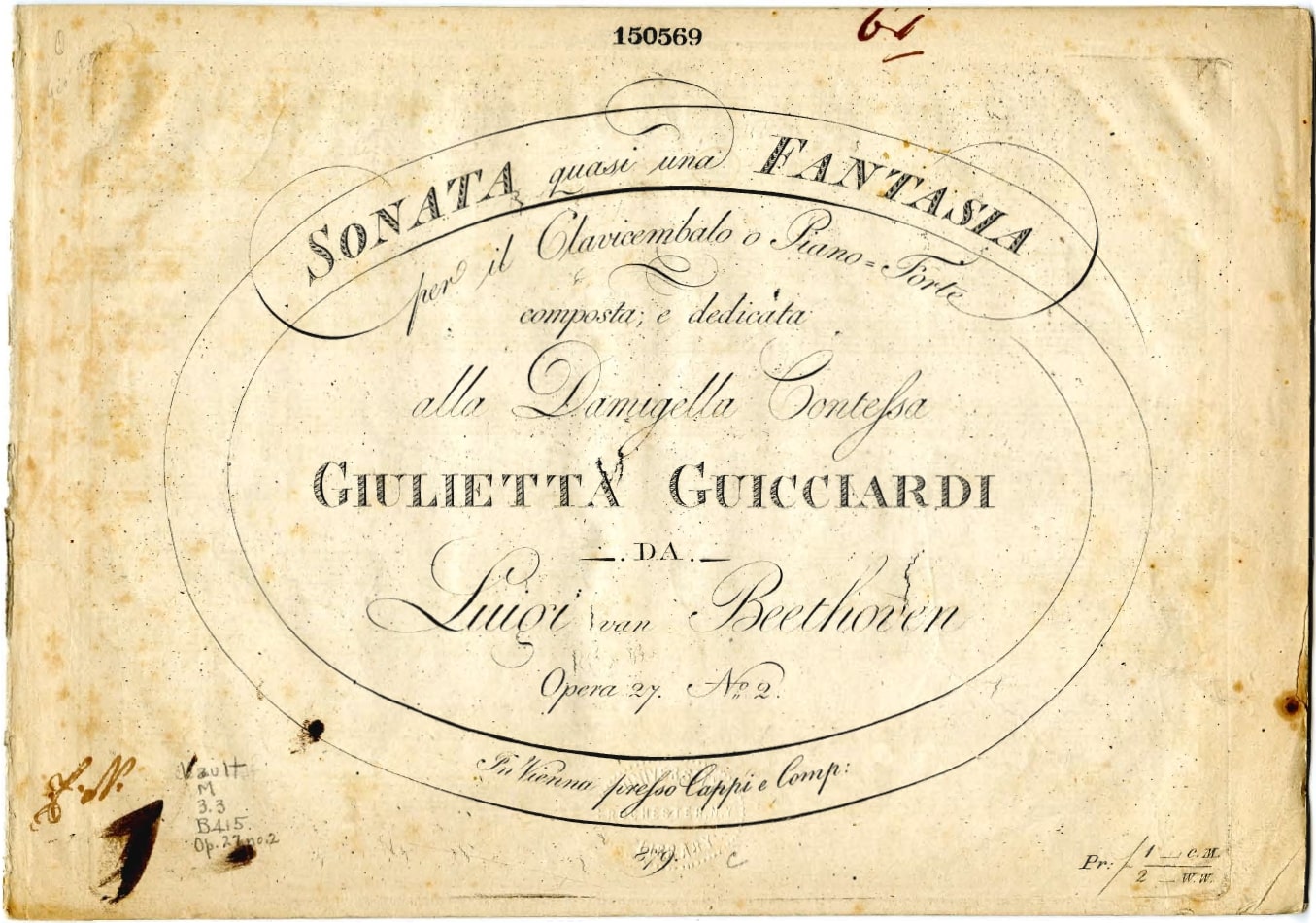

Despite my conductor's fears, the arrival of the Zeta did not mean the end of my classical playing, though it did make me humbly aware of the huge proverbial iceberg of music that lay hidden beneath Beethoven and Mozart.

The electric violin made it possible for me to play in heavily amplified situations free from a fussy microphone and a clumsy mic stand and completely eliminated feedback. Word got out that there was an electric violinist at school and I played in all sorts of bands, from country to heavy metal, jazz to pop and disco to swing.

I soon discovered this violin wasn't limited to playing in loud venues entirely. My Zeta became very useful in studio situations where consistent levels, tone and timbre are required. No microphone is needed here, so engineers don't have to fuss to get the mic in the exact same spot every session and the room doesn't have to have good acoustics. I just plug in my patch cable directly into the main mixer and play, leaving reverb and levels up to the engineer.

Forget the noises of passing trains, cell phones and even the player's breathing into the mic wrecking a good take. This gal stomps to the beat, playing free from headphone or isolation booths, and chatting it up with the engineer between solos. And since Zetas are designed to sound exactly like an acoustic violin rather than a “bowed guitar,” the end result sounds unmistakably like a regular, old-fashioned violin.

Granted, there are things you can do to tweak your violin into sounding quite unlike a violin. I plug into an effects box and play with chorus, reverb and distortion effects. Better yet, Zeta makes the “Synthony,” a synthesizer that converts the violin's analogue signal to MIDI.

Jargon aside, with this tool you can make your Zeta sound like anything from a trumpet to a Chinese gong or any other sound imaginable. With more features than I can list, the Synthony isn't cheap, which explains why I'm still stuck in analogue mode.

Which brings up cost: Even though electric violins have no acoustic body, there is still a vast difference between low and high-end models. Don’t be swindled into buying a cheap $150 “instrument” from anyone, no matter how nice the thing looks in the photo.

Remember that you get what you pay for and electric violins, like any new technology, have become a market for suckers. You wouldn’t buy a $150 stereo system, why’d you buy a $150 instrument and amp? Such “bargains” sound nothing like a violin, feedback terribly when amplified and never last very long due to cheap components. Just like acoustic violins, you’re better off saving up for a good violin rather than throwing good money after bad.

Heck, it’s worth getting a fine electric violin just for the looks you get from other players! I’ve always enjoyed the double and triple-takes I get when I play the Zeta anywhere. I also reserve full bragging rights when speaking to other electric violinists. Denis Letourneau, one of my violin idols in BC, Canada, has a green one-of-a-kind Thompson violin, “Green Dragon.” He’d kill to have a Zeta though, so I’ve always got something to hold over him whenever we talk shop!

As a year-end treat I the Zeta into lessons and teach my violin students about reverb, distortion and the concept of studio recording. Shocked faces, similar to the aforementioned expression of my former conductor, meet the music as concerned parents witness their children creating gruesome variations on their lesson songs.

The kids absolutely love playing on it, especially with distortion and reverb. The shyest of students are rock stars as they bang out a G major scale at full volume. That's the beauty of this instrument: even a scale or arpeggio becomes fun for students.

I usually teach students a pentatonic scale or show them how to pull off power chords in 5ths. This literally keeps them occupied for the entire lesson and they leave only grudgingly. This at the final lesson of the summer when most kids are not at all keen to be indoors or learning scales. They leave the lesson motivated to practice their butts off and prove to their parents they are dedicated enough to deserve one too.

“I've created a monster,” I say to myself, knowing these parents will be inundated with requests for in the car on the way home.

By Rhiannon Schmitt **Rhiannon Schmitt (nee Nachbaur) is a professional violinist and music teacher who has enjoyed creative writing for years. She currently writes columns for two Canadian publications and has been featured in Australia's "Music Teacher Magazine." Writing allows her to teach people that the world of music is as fun as you spin it to be! Rhiannon's business, Fiddleheads Violin School & Shop, has won several distinguished young entrepreneur business awards for her commitment to excellence. Her shop offers beginner to professional level instruments, accessories and supplies for very reasonable prices: Visit http://www.fiddleheads.ca

|